Limburgerhof (The Agricultural Extract-Arrangements), 2008

Installation view at Wilfried Lentz Rotterdam, 2008

Limburgerhof (The Agricultural Extract-Arrangements), 2008

The installation ‘Limburgerhof (The Agricultural Extract-Arrangements)’ is a series of newly produced pieces, – translations and reworkings of material relating to an agricultural research centre.

Formerly a small German village producing sugar beet, Limburgerhof was developed as housing for workers of the chemical giant BASF, later to become an agricultural research centre in 1914. As a division of BASF’s other chemical exploits, the Limburgerhof plant became of key importance in the development of knowledge in the chemical manipulation of crops, including the use of fertilizers.

Beckett takes Limburgerhof as a series of events and facets, a sort of loose tool kit with which to re-arrange and combine, in order to derive new sense. In an installation of paintings, sculptures, embroidery and various objects, an environment is born sitting somewhere between a public communications centre of the Limburgerhof, and craft exhibition of BASF-employees.

‘Limburgerhof’ is a continuation of the extract-arrangement series, following ‘Dalmine (and other industry extract-arrangements)’ and preceding the ‘fire extract-arrangements’.

More about the researchcenter Limburgerhof:

Formerly a small village producing sugar beet, Limburgerhof (Germany) was developed as housing for workers of the chemical giant BASF, later to become an agricultural research centre in 1914. What began as a small community, grew into a healthy population of approximately 10.000, many of whom are currently employed in areas of plant protection, plant biotechnology, fine chemistry and fertilisers.

As a division of BASF’s other chemical exploits, the Limburgerhof plant became of key importance in the development of knowledge in the chemical manipulation of crops, including the use of fertilizers. This involved the synthesis of chemicals such as ammonia, a process perfected by the industrialist-chemist and founder of Limburgerhof, Carl Bosch (the Haber-Bosch process). With an idealistic view and manipulation of plant life, the industrial approach to chemical agriculture meant crops of all kinds would prosper through their new-found predictability and sustainability.

There were however several short-comings in the early days of these experiments, in particular the Oppau explosion of 1921, which occurred when a mixture of ammonium-sulfate and nitrate fertilizer had become compacted in a silo. In attempt to dislodge the mass with small dynamite charges, the load ignited, forming a 90 m by 125 m crater and with it, the death of some 600 people. With an air of seeming clarity and know-how, the company products and publications hold a contrasting and apparent wisdom, – a control of processes reflecting a desire to harness the raw depth of nature.

More about the installation ‘Limburgerhof (The Agricultural Extract-Arrangements

Beckett takes Limburgerhof as a series of events and facets, a sort of loose tool kit with which to re-arrange and combine, in order to derive new sense. Each piece of information is kept dry and unfettered in order for it to remain compatible with another, – each object precious so as to place emphasis on the seemingly peripheral. In an installation of paintings, sculptures, embroidery and various objects presented in cabinets, an environment is born sitting somewhere between a public communications centre of the Limburgerhof, and craft exhibition of BASF-employees. With this technique for the approach of a history, the exhibition aims to become a lens, both to review and offer new light on a subject, as well as to practice a visual language purely as an act in itself.

‘Limburgerhof’ is a continuation of the extract-arrangement series, following ‘Dalmine (and other industry extract-arrangements)’ and preceding the ‘fire extract-arrangements’, of which there will be a few preview pieces on show.

Limburgerhof (The Agricultural Extract-Arrangements), 2008

Installation view at Wilfried Lentz Rotterdam, 2008

Limburgerhof (The Agricultural Extract-Arrangements), 2008

Installation view at Wilfried Lentz Rotterdam, 2008

Limburgerhof (The Agricultural Extract-Arrangements), 2008

Installation view at Wilfried Lentz Rotterdam, 2008

Limburgerhof (The Agricultural Extract-Arrangements), 2008

Installation view at Wilfried Lentz Rotterdam, 2008

Limburgerhof (The Agricultural Extract-Arrangements), 2008

Installation view at Wilfried Lentz Rotterdam, 2008

Limburgerhof (The Agricultural Extract-Arrangements), Sack One and Two, 2008

vitrine with found sack and sculpture as dyptich

100 x 80 x 35 cm (vitrine), 79 x 57 x 26 cm

Limburgerhof (The Agricultural Extract-Arrangements) Key rings, 2008

Vitrine, and Silver Sack key ring, two found key rings

22 x 100 x 16 cm

Silver Sack, 2008

silver key-ring with found chain, on nail

(miniature of larger model)

11 x 3 cm, edition of 10

Limburgerhof (The Agricultural Extract-Arrangements)

Plates and Knives, 2008

Vitrine, 2 dishes, 2 knives

50 x 110 x 24 cm

Unique

Limburgerhof (The Agricultural Extract-Arrangements)

Flowers, 2008

Machine embroidery tryptich

9 x 45 cm each

Ed. 5 + 1 AP

Limburgerhof (The Agricultural Extract-Arrangements)

detail of Flowers , 2008

Machine embroidery. tryptich

9 x 45 cm each

Ed. 5 + 1 AP

Salad Spoons (BASF/Luran), 2008

Vitrine, found cutlery embroidered shirt

50 x 100 x 40 cm

Unique, (shirt in an edition of 5)

Limburgerhof (The Agricultural Extract-Arrangements), Salad Spoons (BASF/Luran), 2008

Vitrine, found cutlery embroidered shirt (detail)

50 x 100 x 40 cm

Limburgerhof The Agricultural Extract-Arrangements

Salad Spoons (BASF/Luran), detail, 2008

Vitrine, found cutlery embroidered shirt

50 x 100 x 40 cm

Unique, (shirt in an edition of 5)

Limburgerhof (The Agricultural Extract-Arrangements), Ashtray One and Two, 2008

Vitrine, wooden sculpture ashtray model, ashtray with BASF-logo

12 x 40 x 28 cm

Limburgerhof (The Agricultural Extract-Arrangements), Wheat One and Two, 2008

Indian ink, gouche and white pencil on paper, dyptich

52,5 x 52,5 cm each (detail Wheat One)

Limburgerhof (The Agricultural Extract-Arrangements), Wheat One and Two, 2008

Indian ink, gouche and white pencil on paper, dyptich

52,5 x 52,5 cm each (detail Wheat Two)

Limburgerhof (The Agricultural Extract-Arrangements), Untitled, 2008

Upside Down BASF Mug in Bavarian mid 19th Century Clockcabinet (detail)

48,5 x 31 x 17 cm

Limburgerhof (The Agricultural Extract-Arrangements), Untitled, 2008

Upside Down BASF Mug in Bavarian mid 19th Century Clockcabinet (detail)

48,5 x 31 x 17 cm

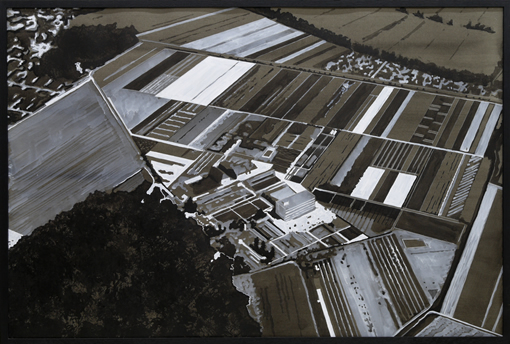

Limburgerhof (The Agricultural Extract-Arrangements)

Gelaende und Gebaeude der Landwirtschaftlichen Versuchstation Limburgerhof (aerial view), 2008

Indian ink, gouache and white pencil on paper

69 x 102 cm

Limburgerhof (The Agricultural Extract-Arrangements)

No Title (Corn), 2009

Indian Ink, gouache in frame

62x90 cm

Limburgerhof (The Agricultural Extract-Arrangements)

No Title (flowers), 2009

Indian ink, gouache in frame

59x153 cm