Monumento ai Caduti, 2010

Intervention and public action at the new venue of the municipality of Bologna Piazza Pubblica in 2010.

photo documentation

Monumento ai Caduti, 2010

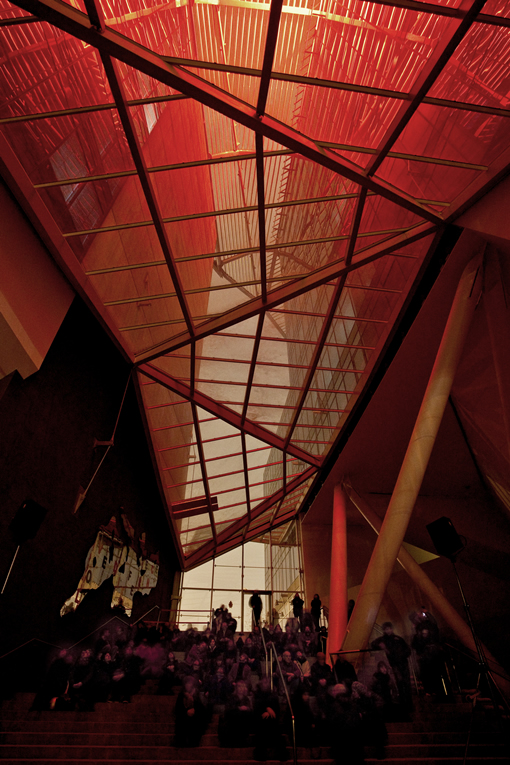

The images documents the night action occurred on January 30 on the roof of the Bologna Municipal building, when a group of inhabitants were asked to rise and light up several torches so as to indicate a warning threshold. Reflecting on the districts’ urban shifts, the intervention turned into a luminous monument in which all the existing lights of that area were progressively switched off in order to let the torch lights transform the architecture in an incandescent body. Seen from great distance, the action was also transmitted from a local radio.

Text by Eva Fabbris:

The etymology of the word “monument” is linked to the Greek root mne-ma, “memory.” Something that is built with the aim of perpetuating a memory (of events, historical figures…) ought logically to last for as long as possible. Perhaps it is in reaction to the areas of grave historical amnesia from which Italy suffers that some Italian artists have begun to reconsider and disrupt the link between time and memory of which the monument is an emblem.

Giorgio Andreotta Calò’s most recent work is called Monumento ai Caduti (Monument to the fallen) (2010). An action staged in Bologna as part of the event “ON, Luci di pubblica piazza,” the work was staged on the evening of January 30 around three new buildings constructed to house the city council and other services. Andreotta Calò asked about thirty people to recount their memories connected with the history of the area. During the action, the audience was able to listen to these stories, reworked by the MEM Music studio abd relayed through loudspeakers scattered around the spaces between the buildings. From the roof tops, some of the people whose voices could be heard continually lit handheld torches that produced a smoky, vermilion light. e stories and this “emergency” lighting were perceivable even by people who were not at the city hall: from a distance, the buildings with fiery roofs must have looked like giant torches.The voices were also broadcast on a radio frequency that could be picked up all over the city. But for those who were there, the combination of lights and voices, along with the gathering of the public in the darkness, created a sensation of vibrant but steady emotion; a sort of quiet requiem, without bombast. For an hour and a half, the building was a monument to what it had replaced—architecturally, emotionally and culturally.

I asked Giorgio to whom the “fallen” in the title referred. He told me, “The fallen are

just the physical spaces. The buildings. Those who frequented these places have just moved.

Or, if they have stayed, are witnesses to a change underway.”

This change affects an area that originally housed the fruit and vegetable market and other public infrastructures, which were moved elsewhere at the end of the 1980s, leaving behind a terrain vague which was taken over by a number of autonomous activities. One of these was the historic LINK, a center for experimentation and shared reflection on the arts to which many leading figures on the Italian art scene of the 1990s made an active contribution. Then came the city council’s decision to take possession of the area again, with the consequent demolition of its buildings. In Calò’s words, “The municipal pharmacies were knocked down and with them LINK, the fruit and vegetable market and other infrastructures. A large area of free and empty space was created. A heap of rubble. The city hall as a sort of white elephant. The city hall as a structure architecturally extraneous to the urban layout of the Bolognina, constructed along the lines of a working-class district. A spaceship that had made an unexpected landing. A space that has not had the time to establish an identity.

“To carry out a work on a building of this kind is precisely to recover an identity.”

One of Calò’s earlier works has particular affinities with the one in Bologna, from the viewpoint of its “iconography” as well as its content. From Twilight Until Dawn (2006) celebrated the situation of impermanence by turning a place in transition into a transitory monument.

From the 18th floor of the skyscraper that housed the Parliament in Sarajevo (which, at that time, following the Bosnian War, had been reduced to a concrete skeleton), he shone a warm, red light, produced by twenty powerful theatrical floodlights. The intensity of this light was designed to reproduce artificially the moment at which the sun is about to vanish or appear on the horizon.

“It represented a zero moment in which the beginning and the end cancelled each other out,” writes Calò. The building, one of the very few skyscrapers to have been left standing after the bombardment, had become a sort of center for the ghost of an urban life in the city. With Calò’s intervention, dedicated to the moment of transition that Sarajevo was living through, the former parliament building took on monumental significance, whose temporal dimension was concentrated in a single night instead of being projected infinitely into the future. There being no stability to commemorate, the monument could not and did not want to aim for eternity.

In the presentation material accompanying the action in Bologna, Calò quoted a passage from the Apocalypse of John as an introductory comment on his project (I know for a fact, moreover, that it is a text Giorgio knows by heart): The opening of the Sixth Seal, which unleashes earthquakes and destruction. The stars fall from heaven and men take refuge in caves. Certainly, buildings are not going to survive.

Monumento ai Caduti, 2010

Intervention and public action at the new venue of the municipality of Bologna, Italy

photo documentation

Intervention and public action at the new venue of the municipality of Bologna, Italy

photo documentation